Problem solving is often thought of as a common-sense skill that children learn naturally through modeling in relationships with caregivers and adults. While some children may develop these skills without much explicit teaching, many children benefit from being taught problem-solving skills directly and systematically, especially when it comes to social problem solving occurring within relationships and social contexts.

Children encounter many challenges throughout the day which require some degree of social problem solving. For smaller things that are easier to deal with, such as having to pick out a different outfit for school when a favourite sweater is dirty, children and their parents may not even recognize that children have employed problem-solving skills because they applied them automatically and without too much thought. For problems that are overwhelming and evoke strong emotional reactions, such as sibling conflict or a falling out with friends, children may have difficulty responding in ways that are helpful and may seek adult intervention to solve these problems for them. Teaching children to become independent problem solvers enhances their ability to cope effectively with minor and major stressors (Nezu et al., 2013). This is an important skill involved in helping children to develop and maintain meaningful relationships, being successful at school, and developing and maintaining positive mental health.

Problem Solving and Mental Health Challenges

Teaching social problem-solving skills is a common therapeutic intervention in child therapy. While children with mental health challenges may not necessarily present with any problem-solving skill deficits, they may not apply these skills as readily or consistently as other children. Anxious children tend to lack confidence in their problem-solving abilities (Creswell et al., 2017), while difficulties making decisions and a sense of hopelessness often make problem solving seem like an insurmountable task for children experiencing depression (Friedberg & McClure, 2015). Impulsivity and difficulties with emotional regulation can also interfere with the application of problem-solving skills making it difficult for children to slow down to stop, think, and plan before responding to stressors.

Developmental Considerations

While we want to help children develop greater independence in their problem-solving abilities, we must also maintain realistic expectations based on developmental considerations. Social problem solving is an executive functioning skill that involves a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex. This part of the brain is still under construction in children and is not fully mature until their mid-twenties (Siegel & Payne-Bryson, 2012). As such, children’s abilities to apply problem-solving skills independently will be inconsistent. Caregivers should be prepared to provide ongoing support and coaching to help children strengthen the connections in their brains involved in social problem solving.

Promoting a Problem-Solving Approach to Life

The first thing we want to help children understand is that problems are a part of everyday life. This can help children approach the daily challenges they encounter as “problems to be solved” instead of catastrophes that they are unable to cope with. When children have a positive problem orientation, they are more likely to be optimistic and believe that problems are solvable, have greater confidence in their ability to solve problems, and recognize that problem solving involves time and effort (Nezu et al., 2013).

While seeking help from adults to solve problems is not necessarily problematic, if parents are too quick to intervene and solve problems for their children to relieve their children’s distress or their own distress that is triggered in response to watching their children struggle, overtime, children can begin to rely on adults to solve their problems for them. This can lead to children developing a negative problem orientation where they view problems as unsolvable threats, doubt their abilities to cope successfully with problems, and become highly frustrated and upset when faced with problems or unpleasant emotions (Nezu et al., 2013).

How to Teach Problem-Solving Skills

Notice, label, and provide praise when children attempt problem solving: Be on the lookout for times when children use problem-solving skills to address minor daily stressors, e.g. finding an alternative when their favourite breakfast cereal isn’t available. Help them become aware of this process by labeling the problem they encountered and naming and praising the steps and skills they used to try to solve it.

“I love how you solved that problem! Your favourite cereal was all gone, and you were REALLY disappointed, but you looked through the other options and chose oatmeal instead. That was a great solution!”

Children’s problem orientation can have a strong impact on their motivation and ability to engage in focused attempts to solve more stressful problems (Nezu et al., 2013). Bringing awareness to their problem-solving abilities by labeling and praising their attempts to address minor stressors can help them develop the belief that problems are solvable and develop confidence in their ability to solve them.

Support children to regulate strong emotions first: When children are overwhelmed by intense emotions this becomes a barrier to effective problem solving. Children need help soothing and settling their emotions and nervous systems before they can be coached to apply problem-solving skills.

Teach the problem-solving steps: Look for everyday challenges that children face and find ways to walk them through these problem-solving steps:

Help them to label or name the problem: Ask, "What is the problem?" Support children to give their problem a name and figure out what is wrong. Help them gather information about the problem while sticking to the facts. Once they have been able to define the problem, assist them in determining what their goal is and what they would like to have happen.

Help them to consider possible ways to solve the problem: Ask, "What are all of the things you could do about it?" It’s important to remain curious and encourage as much independent thinking as possible. Younger children may need help generating possible solutions, however, try to avoid giving older children all the answers or ideas. During the brainstorming process, children may identify solutions that are not realistic or effective. This is not the time to discredit their ideas. They can be gently guided to think about the pros and cons of their proposed solutions in the next step to help them arrive at a decision on their own.

Support them to consider the pros and cons of their proposed solutions: Ask, "What will probably happen if you try each of these possible solutions?" Help children to think about the potential consequences and benefits of each solution.

Encourage them to choose a solution to try out: Ask, "Which solution do you think will work best?" After looking at each of the possible solutions and the desirable and undesirable things that might happen, support children to choose the solution they think will be most successful in solving their problem. Help them put it into action.

Help them evaluate how it went: Ask, "How did it go? How successful were you in solving the problem? What did you learn?" Even if their solution is not successful, it can be framed as a learning experience instead of a failure. It’s simply giving them more information about the problem that can help better inform them as they move through the steps again to determine another solution to try.

Encourage them to try again: Ask, "Given what you learned, is there another solution that might be more effective?" Support children in working through the problem-solving steps again to adjust their plan.

Give Credit: Give children credit for their effort, creativity, and perseverance in solving problems and encourage them to give themselves credit for their attempts at developing and using problem-solving skills.

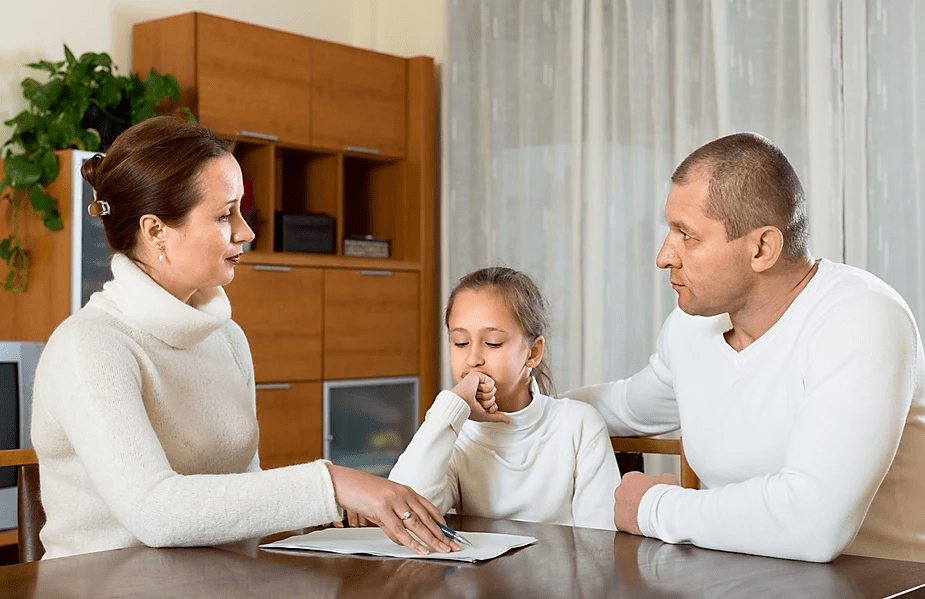

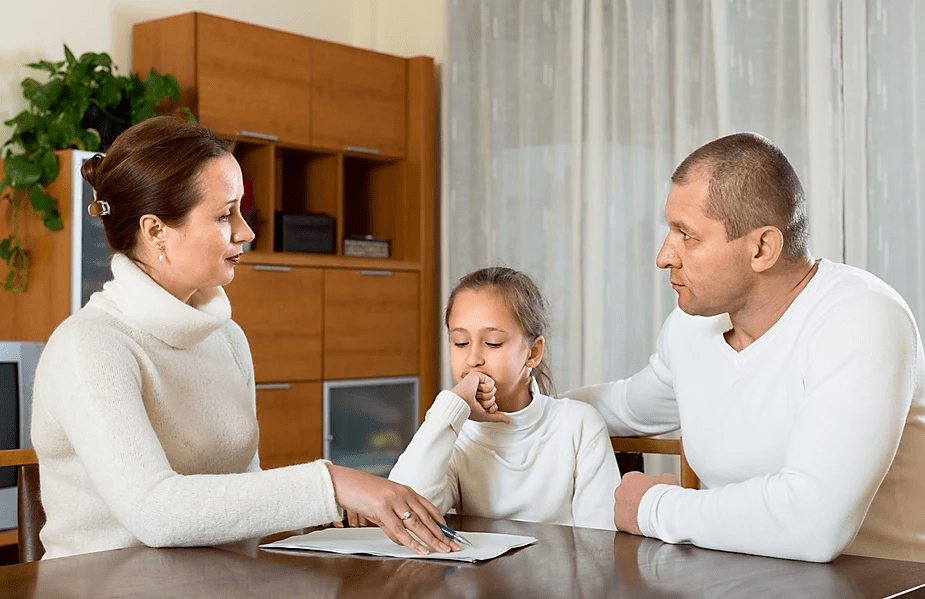

Role model problem-solving skills for children: Children learn new skills and behaviours by observing and imitating others. Parents and caregivers hold the most influence in the lives of young children and are, therefore, in the best position to model these skills for their children. This can be done by talking out loud about the problem-solving steps for the benefit of children when parents encounter challenges.

Parents and caregivers can also facilitate family problem solving to address every day challenges that families face, such as managing the family schedule with everyone's extracurricular activities. Engaging in the problem-solving steps together as a family is a great way to promote a family culture that embraces a problem-solving approach to life. It also supports children to become independent problem solvers and prepares them to be better equipped to face the challenges they encounter in life.

Kari Deschambault MSW, RSW

Mental Health Clinician

MORE COMMON THAN YOU THINK

1 in 7 children suffers from mental illness in Manitoba [6].

70% of mental health problems have their onset in childhood or adolescence [3].

There Is Hope The good news is that mental illness can be treated effectively. There are things that can be done to prevent mental illness and its impact and help improve the lives of children experiencing mental health concerns. Early intervention is best.

How KIDTHINK Can Help To make a referral contact us For additional resources To subscribe to our newsletter click help

Sources:

Creswell, C., Parkinson, M., Thirlwall, K., & Willetts, L. (2017). Parent-Led CBT for Anxiety: Helping parents help their kids. New York: The Guilford Press.

Friedberg, R.D. & McClure, J.M. (2015). Clinical Practice of Cognitive Therapy with Children and Adolescents: The nuts and bolts (2nd Ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Government of Canada. (2006). The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. Retrieved from https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Practice/human_face_e.pdf

Nezu, A.M., Nezu, C.M. & D’Zurilla, T.J. (2013). Problem-Solving Therapy: A treatment manual. New York: Springer Publishing Company: New York.

Siegel, D.J. & Payne Bryson, T. (2012). The Whole-Brain Child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child’s developing mind. New York: Bantam Books.

Virgo Mental Health and Addictions Strategy Report, Manitoba 2018. Retrieved from https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/mha/strategy.html